PTLD Stories of Strength

View More Stories

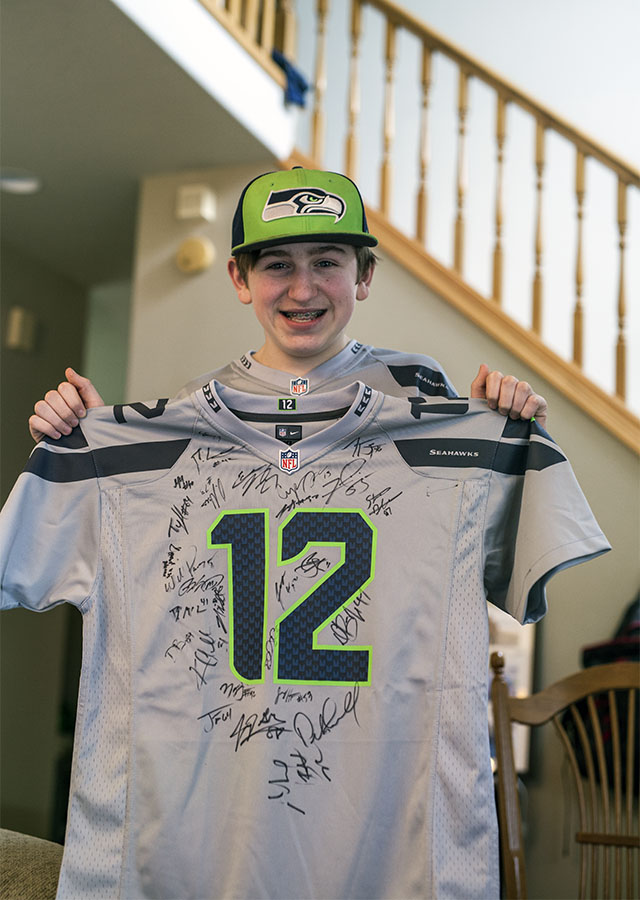

Ayden, PTLD Advocate

Pneumococcal strep A19 survivor

Kidney transplant recipient

Don’t give up. That’s the main thing.

As the sound of Christmas carols floated in from the hallway, the gifts kept pouring into the small hospital room where Ayden and his mother, father, and grandmother all gathered around his hospital bed. Hand-sewn quilts, blankets, and a total of twenty-six hats were donated by various organizations such as the Children’s Cancer Association; the Children’s Healing Art Project brought in carts of painting, beading, and sculpture supplies for the children of the oncology ward. Not one but two Christmas trees filled Ayden’s small hospital room. “It’s a wonder we could even get in the room,” says Virginia, Ayden’s grandmother, laughing. “But all I could think about,” says Ayden, “was leaving the hospital and getting home. I just wanted to be at home.”

At thirteen years old, Ayden had just been diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), a type of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. When Ayden first felt the lump in his belly, there was no thought in his mind it could be cancer, but a CT scan told a different story. It showed a tumor was the size of a man’s fist, wrapped around his bowels.

Ultimately, Ayden’s wish to go home would come true. After taking medication that shrunk his tumor in half, he was, for the first time in two weeks, discharged from the hospital. Loading all the gifts into their car, they were ready to go home. “We came in with one suitcase and had to take home a truckload,” exclaims Bernie, Ayden’s father. The next step for shrinking the remaining tumor was intensive chemotherapy. Every twenty-one days he would return to the hospital and stay in-patient overnight.  Ayden lost his hair, missed school, and hired a tutor to help him academically. “It was rough,” recalls Ayden. Schoolmates teased him for wearing a baseball cap and for his lack of hair. “They were just being mean,” he says in a calm, reflective voice. “I tried not to let it get to me. I didn’t want to tell anyone I had cancer because then they might have made more fun of me.” He had a few good friends who remained close, and while he wasn’t at school, he would stay in touch with them while playing video games on his Xbox. For Ayden, adjusting to medical challenges is firmly interwoven into his persona. He was born healthy until just after his first birthday, he became lethargic and was showing flu-like symptoms. He was admitted to the hospital to get fluids and then one moment suddenly turned blue from the waist down. Ayden’s mother, Carole, knew something was wrong and acted. “I ran out of the room yelling for the doctors,” she explains. “They came in and called code on him.” Carole and Bernie were left standing there, shaken, shocked, and overwhelmed.

Ayden lost his hair, missed school, and hired a tutor to help him academically. “It was rough,” recalls Ayden. Schoolmates teased him for wearing a baseball cap and for his lack of hair. “They were just being mean,” he says in a calm, reflective voice. “I tried not to let it get to me. I didn’t want to tell anyone I had cancer because then they might have made more fun of me.” He had a few good friends who remained close, and while he wasn’t at school, he would stay in touch with them while playing video games on his Xbox. For Ayden, adjusting to medical challenges is firmly interwoven into his persona. He was born healthy until just after his first birthday, he became lethargic and was showing flu-like symptoms. He was admitted to the hospital to get fluids and then one moment suddenly turned blue from the waist down. Ayden’s mother, Carole, knew something was wrong and acted. “I ran out of the room yelling for the doctors,” she explains. “They came in and called code on him.” Carole and Bernie were left standing there, shaken, shocked, and overwhelmed.

They found an infection (pneumococcal strep A19) that caused fluid to build up around his heart, creating the infection in his pleural cavity (between his lungs). “It’s a common bacteria that we all have,” explains Bernie, “but Ayden didn’t have the immune system to fight it. It was a very rare case—the doctors had never seen anything like it.” To remove the infection, the doctors administered a thoracotomy, surgically cutting into his chest—a scar which Ayden still has today. He was given a heart and lung catheter, the infection was cleared, and Ayden was stabilized. Everything seemed to be functional, except for one thing: his kidneys.

With a team of four specialists (a heart doctor, a kidney doctor, a lung doctor, and an infectious disease control doctor), Ayden was monitored very closely. During this time, Bernie and Carole weren’t allowed to hold Ayden for the doctor’s fear of causing too much stimulation. “We could only touch his foot,” recalls Carole, with tears in her eyes. For many years later into his childhood, Ayden would ask for his foot to be held. Sometimes, while driving in the car, from the back seat, Ayden would place his foot towards the front seat. “He would say, ‘will you hold my foot?’ It was never ‘hold my hand,’ it just had to be his foot,” she says. Even though Ayden has no memory of those early days, it was clearly the most comforting gesture that left an impression through trying times as an infant.

After months in the hospital as an infant, Ayden’s body suffered. Born at the 75th percentile in size and weight, he tanked to the 4th percentile. He had lost his ability to sit up. He had forgotten how to walk. While attached to oxygen, Ayden and his parents would practice walking around the PICU.

They were released from the PICU just before Thanksgiving. Ayden was on hemodialysis, a feeding tube, and then eventually, peritoneal dialysis. For ten hours a night, Ayden would be connected to a machine, continually flushing toxins out through his peritoneum. A G-tube fed him at night. Ayden’s nausea was so severe that he threw up every day, continually, for a few years. “Dialysis patients often have a metallic taste in their mouth, so he didn’t want to eat,” says Carole.

Ayden’s parents tried everything they could to donate one of their kidneys to him, but during Carole’s very last approval test, she found out that she herself had a rare autoimmune lung disease making it inadvisable for her to donate her kidney. She would need both her kidneys intact in the case she ever needed a lung transplant. They were told that a kidney suitable for transplant could be found within nine months to a year maximum. They had no choice but to wait.

A Priceless Gift

Three long years later, a match was found for Ayden. The match was five-sixths—a good one, from a 23-year-old. The family made it to the hospital in time for surgery, and Ayden’s new kidney was implanted right away. “When kidneys are transplanted, they are placed on the front of the body and backwards,” explains Bernie. “His old kidneys are still there, but they tie the new kidney in.” To protect his new kidney, Ayden started wearing a protective pad around the front of his body.

For Ayden’s new kidney, they had to choose between two medications to give him, one with a higher chance of rejection, the other with a slight risk (4% chance) of cancer. “It’s a horrible choice you have to make,” says Carole. “You just hope the odds are in your favor.” They made their pick, choosing the medication with the small risk of cancer. Life continued on for ten years as normal, until the Christmas when Ayden found the lump in his belly. It was revealed that it was non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, caused by PTLD (Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease), from his kidney transplant.

Throughout the entire process, the oncologists had to continually consult with nephrology, maintaining as fine a balance as they could, as they did not want to impair Ayden’s kidney at any point. “You have to balance medications, kidney function, and liver enzymes to make sure the kidney is still functioning well,” explains Carole. During chemotherapy, they were able to stay in-patient overnight to hydrate Ayden thoroughly, and fortunately, his new kidney managed just fine.

Finding a New Normal

Although Ayden missed school during chemotherapy, getting to go home meant that he would not miss his karate practice. Since the third grade, he’s participated in a martial arts program three days a week after school. He’s now in his seventh year and a junior black belt, destined to attain his actual black belt in two years. During chemotherapy, he was not able to participate in the practice, but he would still show up to be present. “I’d say if his numbers were up [blood counts], we would go to practice,” says Carole. “I’d remind Ayden that if one of the Seahawks players [Ayden’s favorite football team] gets injured, they don’t just go home and watch TV. They are right there on the sidelines. They are part of the team.” So, every other day after school, Ayden would go to his martial arts practice and would either step in for ten minutes or would remain an observer. He was dedicated and wanted to be there. “I just kept thinking, don’t get behind,” remembers Ayden. “I was proud of him for that. It showed strength,” says Carole.

After having cancer it feels like I have less stress, like I’m not worrying about what’s gonna be next after each treatment. Now I can relax.

The martial arts program gave their students life homework, themed on perseverance, excellence, focus, and respect. Ayden would have to reflect those qualities at his school as well. His martial arts community gave him a peer group, strong mentors, confidence, and morale. No doubt it helped him get through a deeply challenging time in his early teenage life.

Don’t give up. That’s the main thing. There’s always some type of help.

Don’t give up. That’s the main thing. There’s always some type of help.

Three weeks after the last chemotherapy appointment, the doctors announced that Ayden’s cancer was in remission. It has now been a full year since that moment, and his only scheduled treatment is next year, when he will spend a full day with a team of health specialists including doctors, nutritionists, and psychologists. “Oh, I hope it’s not during a school day,” groans Ayden. “I don’t want to miss any high school!”

It’s almost Christmas again, and Ayden is looking forward to spending a relaxing evening at home sharing a home-cooked meal with his parents, grandmother, aunt and uncle, and their beloved dog. “After having cancer,” says Ayden, “it feels like I have less stress, like I’m not worrying about what’s gonna be next after each treatment. Now I can relax.” In a year, he has truly come a long way. In overcoming several life-threatening medical conditions, Ayden hopes to inspire kids who’ve faced seemingly insurmountable health challenges with courage and compassion. “If I were to meet someone who was going through what I did, I’d say, ‘Don’t give up. That’s the main thing.’ There’s always some type of help.”